We Should Do This Again Sometime Fight Club

the first rule

Fight ClubSpoke to Me

Twenty-five years subsequently, a novel that shouldn't have resonated nonetheless does.

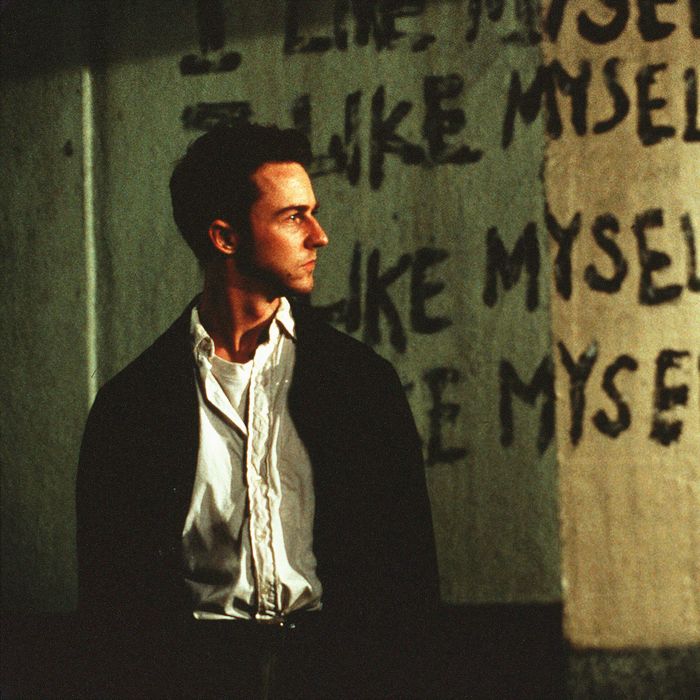

Photo: 20th Century Fox/Kobal/Shutterstock

Photo: 20th Century Flim-flam/Kobal/Shutterstock

Photograph: 20th Century Fox/Kobal/Shutterstock

A few months agone, a friend and I were hanging out beside an abandoned baseball field reflecting on the hypermasculine activities we loved earlier nosotros came out. I, for instance, loved — "loved" — paintball and Maglites and Anna Nicole Smith, and I continue to fawn over unhinged action movies, those of the Cruise and Cage variety. I obsessed over these things partly to hide my ongoing doubt near my assigned gender identity. My strategy was simple: Like something masculine coded, convince anybody I was a male child, including myself. As a teenager, I loved the novels of Chuck Palahniuk, peculiarly Fight Club, the essential book about the nihilistic rage of bumming men. That made perfect sense to my friend only non for the reasons I expected. "I knew so many so many trans people who loved Fight Gild before they came out," she said, and then nonchalant I felt as if I should take already known. After a few weeks' obsessing over her comment, I bought a new copy of the novel. I had donated my original a decade agone.

Perhaps there'due south a simple explanation for trans people loving Fight Society: A lot of people loved Fight Gild. But I'm convinced there'south a deeper, less immediate reason. Transformation plays a vital role in the novel. The men who join Fight Guild seek to eradicate everything superficially male about their lives — admitting through hypermasculine tactics — and the person you run into in Fight Lodge, the narrator states, "is not who they are in the real world." Fight Order does ii things very well. Information technology captures the colicky malaise of men, and it pursues a truth that is hard to face up: We would similar to exist someone else. Before I came out equally trans, this was not a truth I could avoid.

Information technology has been 25 years since the publication of Fight Club, and its affect remains like shooting fish in a barrel to spot: Fight Club chapters have sprouted up across the world over that time, academics have debated the novel at conferences and performed interpretive dances, and yous've probably heard someone say "The First Dominion of [blank] is don't talk nigh [bare]" more than times than you intendance to remember. Just viii months agone, the U.S. faced an attack on the Capitol building led by and large past angry white men looking to reappoint their leader to part. Derailing the democratic process is a fitting task for Projection Mayhem, the cult that evolves out of Fight Club.

I showtime came to Fight Club the manner many people did: through the movie. The summertime I turned 12, my older cousins named all their video-game characters Tyler Durden. I was eager to get the reference — they refused to explain it to me — so I ordered the picture show through my mom's satellite subscription. It did not instill in me a want to fight or become a Existent Man. The literal physics of the final gunshot confused me. How could someone kill his persona past shooting himself in the oral fissure? I looked to my cousins for answers. They insisted the movie was but as well smart for me.

Fight Club reentered my life in high school when I enrolled in a form called "Filming the Novel" — it was the hottest (easiest) course in schoolhouse. The semester consisted of reading novels, then watching the adaptations before taking quizzes noting the differences betwixt the films and the books.

In loftier schoolhouse, I spent my afternoons at Borders listening to sample tracks from indie bands and splurging on Wes Anderson DVDs. The literature section, even so, seemed like a threateningly feminine infinite — my best friend was a girl, and she read all the time — just Fight Club gave me an alibi to drift among the book aisles, flipping through the opening capacity of Palahniuk'south Choke and Survivor before testing out other books that had been adapted into movies: Alex Garland's The Embankment, Bret Easton Ellis'southward The Rules of Attraction and American Psycho. In Palahniuk'south books, nothing ever went unsaid. Every purile and wretched thought seemed to make it onto the page. As a teenager fenced in by curfews and homework and groundings, I was enamored of anything that flouted social conventions, and as a pretentious teenager, I loved finding these ideas in novels. You might expect me to say I was drawn to Invisible Monsters, Palahniuk's novel almost trans style models; after reading the flap copy, though, I avoided the book. I feared what reading it might say nearly me. But the sight of information technology made my breadbasket tighten with shame.

In college, I decided to become a Serious Author and abandoned Palahniuk. As I vicious for the work of Mavis Gallant and Deborah Eisenberg and James Baldwin and others, my love for novels like Fight Club embarrassed me. How could something so pulpy and corny spur my beloved of reading? But I've come to accept that we rarely get to cull what speaks to us on a subcutaneous, languageless level and that hiding my love for the novel meant hiding something essential nearly me. Since childhood, I had been adept at hiding essential parts of myself, fearing friends and family unit and partners would abandon me if they knew who I was. And who was I? A author who loved pulpy Palahniuk novels. A Ph.D. pupil who skipped course to watch basketball game games. A nonbinary person pretending I was a man.

While writing my novel, The Atmospherians, I began to accept that I could no longer hide. Over the first few drafts, I was living in Houston, married and assumed cis, just on the rare weekends I spent on my own, I would toss on dresses while revising scenes in "an attempt to understand" Sasha, the female narrator of the book. At to the lowest degree, that's what I would have told my wife if she came home or if a neighbor spied me through the windows. But I knew why I was wearing the dresses. I didn't want to understand Sasha. I wanted to exist myself.

My novel is nearly a pair of friends, Sasha and Dyson, who create a cult to reform problematic men. When I started the book, I set out to imagine a less destructive form of masculinity, to plough Fight Guild on its caput. Palahniuk'southward vision of masculinity suggests that an accurate man — the true man underneath the bourgeois facade — can emerge through violence and cocky-cede. I wanted to believe in the opposite, that, through writing, I could create a version of masculinity a human would want to inhabit. Just my problem was never my style of manhood or that I hadn't yet become the right blazon of man; it was that people assumed I was male and that I encouraged this out of convenience and fright. Every bit I revised my novel, I became less interested in reimagining masculinity than in dropping my performance of manhood. My excuse — that I dressed femme to sympathize Sasha — became also taxing to harbor. 7 months earlier I finished the book, I came out to my partner and loved ones as trans.

I did not gear up out to write a trans novel, and many readers would say that I oasis't. My book does not center trans characters — though some have read Dyson's babyhood as that of a closeted trans woman — and in terms of representation, information technology has little in mutual with novels like Detransition, Baby and Summer Fun and Confessions of the Fox and Future Feeling. But the novel unconsciously expresses my desire to escape the gender binary. In The Atmospherians, characters suffer because people in their lives have imposed strict gender expectations upon them. That gender is a vehement operation is hardly an original concept. Encounter: Butler, Judith. But every bit Jeanne Thornton, author of Summertime Fun, told me recently, information technology was obvious to her that the book was "fucking trans" only a few chapters in. Another trans reader described the novel every bit "ooz[ing] dysphoria."

Fight Gild also oozes dysphoria. The hypermasculine aspects of the novel haven't vanished since I read it at 17. In that location remains something unnervingly fratty in both the tone and the plot. Men raised by women who are tired of discussing their feelings come together through violence and terrorism. Palahniuk's instructions for building bombs and rendering soap and deflecting class-action lawsuits all give off — I'chiliad sorry — a mansplain-y vibe. The members of Projection Mayhem are encouraged to buy guns. Naught says "man" similar a gun.

However, as I reread Fight Gild this summertime, the narrator's longing for a more authentic life spoke to my lifelong gender dysphoria. I too harbored a clandestine; I presided over a club of 1 that I refused to e'er discuss. Who I was when I wore dresses was not the person who entered the world to teach or catch drinks.

Twenty-5 years after the novel's publication, nosotros continue breaking the first dominion of Fight Club. That's not considering the book expertly captures the nihilistic resentment of existence a man or because it is cryptically trans. Fight Lodge takes for granted an inexhaustible fright of modern life: We are non who we nowadays to the earth. In the volume, this fear draws the narrator toward gruesome extremes from which he cannot recover. In my own life, this fright helped me cover the person I wished to get. Over the past year, I have, gradually, found a Durden-esque confidence wearing the types of dresses the narrator'southward love involvement, Marla Vocaliser, might steal from a laundromat. For the commencement time in my life, who I am for the world aligns with the person I once refused to talk over.

Source: https://www.thecut.com/2021/08/why-fight-club-is-about-transformation.html

0 Response to "We Should Do This Again Sometime Fight Club"

Post a Comment